Most of the hunters (academic researchers) searching for consensus in their Delphi research, are new to the sport. They believe that they must bag really big game or come home empty handed. But we don’t agree. In fact, once you have had a chance to experience Delphi hunting once or twice, your perception of the game changes.

Consensus is a BIG dilemma within Delphi research. However, it is generally an unnecessary consumer of time and energy. The original Delphi Technique used by the RAND Corporation wanted to aim for consensus in many cases. That is, the U.S. government could either enter an nuclear arms race or not; there really was no middle ground. Consequently, it was counterproductive to build a technique that could not reach consensus. It became binary: reach consensus and a plan could be recommended to the president; no consensus, and this too was useful, but less helpful, to inform the president. (The knowledge that the experts could not come up with a clear path forward, when exerting a structured assessment process, is also very good to know.)

Consensus. The consensus process – getting teams of experts to think through complex problems and come up with the best solutions – is critical to effective teamwork and to the Delphi process. In most cases, however, it is not necessary – or even desirable – to come up with the one and only best solution. So long as there is no confusion about the facts and the issues, forcing a consensus when there is none is counter-productive (Fink, Kosecoff, Chassin & Brook, 1984; Hall, 2009, pp. 20-21).

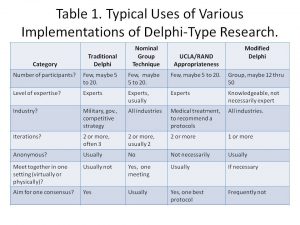

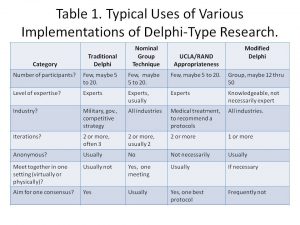

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of various types of nominal group study techniques (Hall & Jordan, 2013, p. 106). Note that the so called traditional Delphi Technique and the UCLA-RAND appropriateness approaches aim for consensus. The so call Modified Delphi might not search for consensus and might not utilize experts. Researchers use the UCLA-RAND approach extensively to look for the best medial treatment protocol when only limited data is available, relying heavily on the expertise of the doctors involved to suggest – sometimes based on their best and informed guess – what protocol might work best. The doctors can only recommend one protocol. Consensus is needed here.

(Table reprinted with permission Hall and Jordan (2013), p. 106).

But consensus is rarely needed, although it is usually found, to some degree, in business research, and even in most academic research. For example, the most important factors may be best business practices. Of the total list of 10 to 30 factors, few are MOST important. Often, the second round of Delphi aims to prioritize those qualitative factors identified in round 1. There factors are usually natural separation points between the most important (e.g. 4.5 out of 5), those that are medium important (3 out of 5), and the low importance factors.

Those researchers who are fixated on consensus might spend time, maybe a lot of time, trying to find that often elusive component called consensus. There are usually varying levels of agreement. Five doctors might agree on one single best protocol, but 10 probably won’t, unanimously. Interestingly, as the number of participants increase, the ability to talk statistically significantly about the results increases; however, the likelihood of pure, 100% consensus, diminishes. For example, a very small study of five doctors reaches unanimous consensus; but when it is repeated with 30 doctors, there is only 87% agreement. Obviously, one would prefer the quantitative and statistically significant results from the second study. (Usually you are forecasting with Delphi; 100% agreement implies a degree of certainty in an uncertain future, essentially this can easily result in a misapplication of a very useful planning/research tool.)

This brings us to qualitative Delphi vs. a more quantitative, mixed-method, Delphi. Usually Delphi is considered QUAL for several reasons. It works with a small number of informed, or expert, panelists. It usually gathers qualitative information in round 1. However, the qualitative responses are prioritized and/or ranked and/or correlated in round 2, round 3, etc. If a larger sample of participants results in 30 or more respondents in round 2, then the study probably should be upgraded from a purely qualitative study to mixed-method. That is, if the level of quantitative information gathered in round 2 is sufficient, statistical analysis can be meaningfully applied. Then you would look for statistical results (central tendency, dispersion, and maybe even correlation). You will find a confidence interval for all of your factors, those that are very important (say 8 or higher out of 10, +/- 1.5) and those that aren’t important. In this way, you could find those factors that are both important and statistically more important than other factors: a great time to declare a “consensus” victory.

TIP: Consider using more detailed scales. As 5-point Likert-type scale will not provide the same statistical detail as a 7-point, 10-point or maybe even a ratio 100% scale if it makes sense.

Subsequently, in the big game hunt for consensus, most hunters continue to look for the long-extinct woolly mammoth. Maybe they should “modify” their Delphi game for an easier search for success instead . . .

What do you think?

References

Hall, E. (2009). The Delphi primer: Doing real-world or academic research using a mixed-method approach. In C. A. Lentz (Ed.), The refractive thinker: Vol. 2: Research Methodology, (pp. 3-27). Las Vegas, NV: The Refractive Thinker® Press. Retrieved from: http://www.RefractiveThinker.com/

Hall, E. B., & Jordan, E. A. (2013). Strategic and scenario planning using Delphi: Long-term and rapid planning utilizing the genius of crowds. In C. A. Lentz (Ed.), The refractive thinker: Vol. II. Research methodology (3rd ed.). (pp. 103-123) Las Vegas, NV: The Refractive Thinker® Press.